One way to prevent future mass shootings, President Donald Trump suggested Monday, was to take a firm stance against violent video games.

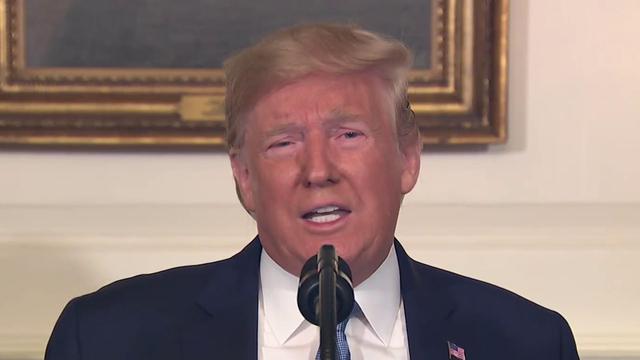

"We must stop the glorification of violence in our society. This includes the gruesome and grisly video games that are now commonplace. It is too easy today for troubled youth to surround themselves with a culture that celebrates violence. We must stop or substantially reduce this and it has to begin immediately," Trump said in brief remarks from the White House after massacres in El Paso, Texas, and Dayton, Ohio, killed at least 31 people over the weekend.

Trump wasn't the only politician focused on video games in the wake of the recent gun violence — and this isn't the first time he's posited a link between mass shootings and brutal video games. Over the weekend, conservative lawmakers, including Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., also suggested video games were to blame for real-world violence.

"We've always had guns, always had evil, but I see a video game industry that teaches young people to kill," Patrick said on "Fox and Friends" Sunday morning, pointing out that an anti-immigrant screed authorities believe is connected to the suspect in the El Paso massacre referred to “Call of Duty,“ a first-person shooter game.

But researchers told NBC News there is no evidence that violent video games encourage violence in real life. And they've definitely been looking. Consider this 2019 study out of Oxford University, which found no link, or this one from 2018 that also found no evidence to support the theory. Studies in 2016 and 2015also failed to find evidence that video games spurred violence, and researchers even noticed signs that crime may be reduced by violent games.

“There's absolutely no causal evidence that violent video game play leads to aggression in the real world,” said Andrew Przybylski, a researcher at Oxford University who has been studying the psychological effects of video games for more than a decade and co-authored that 2019 study.

Earlier this year, Przybylski published his study in the Royal Society Open Science that monitored video game use, as reported by approximately 1,000 British teenagers, and symptoms of aggression, as reported by their parents.

“We found a whole lot of nothing,” he said.

James Alan Fox, a Northeastern University criminology professor and author who has written extensively about mass murders, said the attention to violent video games in the aftermath of shootings is “an easy scapegoat.”

Fox said researchers have identified common characteristics of mass murders, including isolation, failure and a tendency to blame those failures on other people. Video games appear only anecdotally.

The Sandy Hook shooting perpetrator, Adam Lanza, liked violent video games, but he also liked the music video game “Dance Dance Revolution,“ he said.

Others, too, don't fit the model: The Las Vegas shooter had no known video game ties and the Virginia Tech shooter played “Sonic the Hedgehog.”

That violent people may enjoy violent entertainment, Fox said, wasn’t surprising — but it also wasn't a motivating factor.

“If it really was that kind of a cause, given how many millions immerse themselves in video games, we’d had a lot more problems,” Fox said.

According to Pew Research, 43 percent of Americans say play video games; 72 percent of young men say the same. Juvenile crime has fallen as the number of video game players has risen.

Fears about the effects of violent video games grew in the mid-1990s, when video games started depicting blood and carnage. Then-Sen. Jeff Sessions, a Republican from Alabama, blamed violent video games for the deadly shooting at Columbine High School in 1999. Groups like the American Psychological Association (APA) reviewed early studies and recommended the restriction of violent video games in a 2005 resolution.

But violence is a tricky thing to study in a lab, and experts have argued that bias and other issues undercut studies that have appeared to find links between bloody games and real-world aggression. When the APA issued further video game recommendations in 2015, hundreds of researchers, including Przybylski and Fox, signed an open letter that criticized the methodology and biases of the studies that the group chose to cite. The Supreme Court ruled in 2011 that there was no evidence that violent video games motivated real life violence in an opinion authored by Justice Antonin Scalia, when Democrats tried to ban the sale of violent video games to kids.

Przybylski said his research has found that the player experience mattered more than the game's content, violent or otherwise. In one study published in 2014, he rigged Tetris to be an extremely difficult game and observed measurable symptoms of aggression from players.

"The content of the games isn’t nearly as important as the structure of games — even if a game is violent, if you’re good at it, you have fun," he said. "We made people really, really mad with Tetris."

Chris Ferguson, a psychology professor at Stetson University who also signed that open letter to the APA, also said he has not found causation between violent games and violent behavior in his years of research.

“The funny thing about Trump’s comments is we just did this last year — in 2018 after Parkland. His administration commissioned a school safety commission and I testified at it and a bunch of other people testified it. The conclusion from the commission was just ‘eh’ on the topic of video games,” he said.

That Trump commission had the Department of Education and Secret Service team up to produce a report about school safety, but the group’s recommendations about video games did not mirror the president’s own rhetoric on video games as a violence motivator.

"It’s outright weird that the president brings it up... when his own commission didn’t support this narrative," Ferguson added.

The nation's continued focus on video games as a source of violence isn't productive, he added.

“This is only going to distract us from real causes of violence," he said.