Updated at 1:48 p.m. on August 5, 2019.

In the two decades since Columbine, video games have taken a lot of the blame for mass shootings. The evidence has never supported this conclusion, and researchers have become only more certain that media don’t cause violence, or even aggression. Nevertheless, the idea persists. Just hours after a horrifying shooting—including the one that left 22 people dead in El Paso, Texas, on Saturday—someone will blame video games.

But in the past two years, something has changed. Games have shifted from a broad cultural enemy—a gory medium that all types of people might hold responsible for social disgrace—to a political tool. Video-game violence was once a bipartisan worry. Now it’s a largely Republican talking point, deployed for tactical political gain to great effect.

Read: Why video games don’t correlate to gun violence

Before the 2000s, research on the effects of video-game violence on players amounted to a couple dozen studies, tops, estimates Christopher J. Ferguson, a Stetson University psychologist whose work disproves causal connections between video games and violent acts. At that time, the “violent” video games chosen for study were far more rudimentary than today’s games. They included titles such as Zaxxon and Pac-Man—arcade and computer games that barely represented anything realistically, let alone violent acts—and the experiments were as rudimentary as the graphics. Typically, researchers would invite subjects to play a violent game such as Centipede and then compare their post-play “aggression” with that of a control group. Others asked the same questions via surveys alone.

These studies were modeled after earlier research into whether gory television shows could be linked to increases in violent crime. At first, those studies were equivocal, according to Ferguson. But that changed by the 1970s. Perhaps because the actual murder rate was rising, scholarship on the subject started shifting from inconclusive to absolutely certain that television caused violence—even if only by means of a correlation with aggression.

As subjects of study, video games complicate matters. They aren’t captured on film, like television, so the definition of “violence” in a game has always remained abstract: Is eating a Pac-Man monster violent? What about firing a dot at an insect abdomen in Centipede? Ferguson says the results of early video-game studies were all over the place. Some found effects; others didn’t. But, he told me, “people were honest”: Researchers acknowledged the limitations of the studies and the inconclusiveness of their results.

By the 1990s, the tide had turned. Computer graphics, though still relatively simple, were becoming more realistic. The industry also began targeting the now-older kids (and young adults) who had made up the Atari and Nintendo generations of the prior decade. Soon enough, concerns about violent video games also reached Washington. In 1993 and 1994, Senators Joe Lieberman and Herb Kohl—both Democrats—convened hearings about violent games and their possible effects on children. The interest had been sparked largely by Mortal Kombat, a fighting game with realistic and gruesome details, including spurting blood and decapitation. In the aftermath of the hearings, Lieberman introduced legislation to create a rating commission for games; instead, an independent group, the Entertainment Software Rating Board, was established, the games equivalent of the Motion Picture Association of America.

Then, in 1999, Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris killed 13 people and injured 20 more at Columbine High School in Colorado. During the investigation, it became clear that the two had played and enjoyed Doom, the 1993 game that essentially invented the first-person-shooter genre. Klebold and Harris seemed to have used it as a tactical tool, creating maps to plan their attack. The unique shock of the attack might have accelerated interest from behavioral scientists, Ferguson speculated. “After Columbine,” he said, “the honesty stopped.”

Games also became rapidly more mature in their themes and audiences. Grand Theft Auto added misogyny and criminality atop the violence. Doom’s progeny, such as Counter-Strike and Call of Duty, added human enemies and military themes. Video games had incited moral panics for decades by this time—from concerns about driving over stick figures in 1976’s Death Race to the lurid draw of the video arcade in 1982 to the gore in Mortal Kombat in 1993. Inside the community that played them, the changes seemed evolutionary—and the players had grown older, besides. But from the outside, among those who didn’t understand video games, the early 2000s represented a definitive shift toward moral depravity.

In 2005, then-Senator Hillary Clinton co-sponsored the Family Entertainment Protection Act (FEPA) with Lieberman. Among other things, the bill pledged to enact criminal penalties for selling games to minors, and emboldened the Federal Trade Commission to investigate misleading ratings. Clinton became an enemy to games, portraying the form—or at least part of it—as a sin industry: “We need to treat violent video games the way we treat tobacco, alcohol, and pornography.”

Then, in 2007, Seung-Hui Cho killed 32 people and wounded 17 more at Virginia Tech. There had been plenty of mass shootings since Columbine, but none nearly as deadly. Before the dust had settled, Jack Thompson, a Florida attorney who had made a name for himself based on public opposition to violent games, connected the shooting to video games, especially Counter-Strike. Dr. Phil also blamed games, in part, saying that they glamorized mass killing sprees. As with Columbine and FEPA, the opposition was broad and nonpartisan: A distaste for video games was a matter of cultural rather than political disfavor.

By this time, there was already some pushback against the research that was partly inciting the crusades of Lieberman, Clinton, and Thompson. “People were saying, ‘Wait a minute, a lot of these studies are kind of crappy,’” Ferguson told me. The Virginia Tech massacre poured some cold water on the rage, too. Cho’s roommate quickly reported that he had never seen the man play video games, let alone titles that glorified firearms. An investigation later revealed that the most violent game Cho had played regularly was Sonic the Hedgehog.

Read: Could taxing violent video games actually save lives?

In 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court finally got to weigh in on violent video games. The case, Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, affirmed that a California law restricting the sale of violent games violated the First Amendment. Game creators and players celebrated the verdict as an endorsement of games’ status as speech. But the case also defanged much of the research on video-game violence. “The State’s evidence is not compelling,” the decision reads. “These studies … do not prove that violent video games cause minors to act aggressively … and most of the studies suffer from significant, admitted flaws in methodology.”

The next year, when Adam Lanza shot and killed 20 children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School, video games were again blamed in the media. But on the ground, nobody ever seemed to consider the likelihood that games had driven Lanza to murder. As vice president, Joe Biden convened an inquest of the games industry after Sandy Hook, but it was hardly the witch hunt that Clinton had taken on earlier. According to Ferguson, who reviewed hundreds of pages of documentation released from the investigation, law-enforcement representatives even started reporting that they had begun dissuading victims’ families from paying attention to “hoax theories” of video-game violence. When the official reports finally came out, it turned out that the game Lanza had played most was Dance Dance Revolution, an electronica dance-performance game popular at miniature golf courses and bar mitzvahs.

By this time, the replication crisis in the behavioral sciences had begun to undermine studies like the ones already scorned in the 2011 Supreme Court decision. The whole notion of automatic human learning—the idea that people change their behavior in relation to environmental factors they don’t even notice—began to unravel. Within a few years, two papers on video-game violence from one Ohio State University lab were retracted.

Ferguson insisted that the debate about video-game violence will live on as long as there are video games to play and researchers to study them. “But the evidence is very clear that there’s not a relationship between violent video games and violence in society. There’s not evidence of a correlation, let alone a causation,” he said. Other researchers have come to the same conclusion, and the American Psychological Association’s media-psychology division issued a public statement in 2017 discouraging politicians and journalists from connecting games and violence. In his own recent studies on longitudinal behavior, Ferguson and his collaborators have concluded that violent games don’t appear to predict anything useful about violent thoughts or acts—not physical aggression, social aggression, or even cyberbullying.

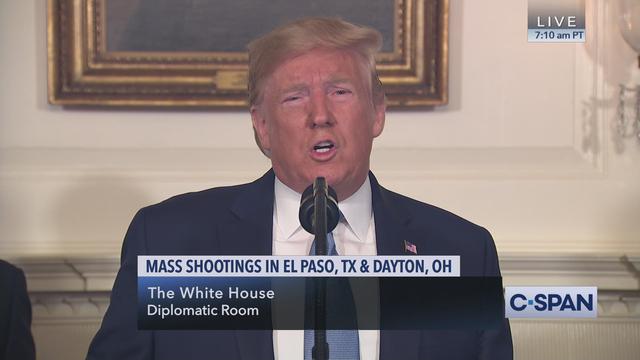

Despite all this, by the time of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, violent video games had reappeared as an explanation for horrific, real-world violence. But something was different—the issue had become almost entirely a partisan one. President Donald Trump blamed violent video games for the massacre, setting off a media frenzy of follow-ups. The South Florida Sun Sentinel claimed that “violent video games may have primed the Parkland school shooter,” dredging up old research and garnishing it with anecdotes from friends and family of Nikolas Cruz, the shooter. Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin launched a miniature crusade to turn blame toward video games (and, not coincidentally, away from guns). The White House compiled a supercut of video-game scenes meant to inspire disgust.

Eventually, the Trump administration’s Federal Commission on School Safety released a report that mostly affirmed the lack of evidence that violent games have any impact on mass shootings. Even so, the appeal of the video-game excuse has only risen since 2018. In the aftermath of the El Paso shopping-center shooting, GOP lawmakers and pundits couldn’t start talking about violent games quickly enough. Fox News speculated that violent video games inspire too much satisfaction. House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy inspired a Fox chyron: “Shooting video games are a problem.” Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick claimed that the video-game industry “teaches young people to kill.”

Read: Why is there a “gaming disorder” but no “smartphone disorder”?

This framing has obvious political benefits. The National Rifle Association started pointing fingers at games after Sandy Hook, and it redoubled its efforts to use the medium to draw attention away from gun possession and gun control after Parkland. Video-game violence seems to have transformed from an issue of bipartisan and earnest cultural opprobrium—video games are gross and maybe harmful—to a sacrificial lamb slaughtered in the service of preserving gun rights.

That’s produced a contrarian response from Democrats. After the barrage of video-game detractions wound through the airwaves, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez tweeted, “Video games aren’t causing mass shootings, white supremacy is.” Outside the political sphere, others have noted that violent video games are sold worldwide, but that only the United States possesses the surplus of firearms that actually carry out gun violence.

None of this is great news for the video-game industry or players. Ocasio-Cortez and others aren’t endorsing games, or even defending them. They are merely rebutting the idea that violent games offer a credible explanation for mass shootings, then refocusing attention on the issues that matter to them—gun control, and now, often, white supremacy. Video games have become a patsy for both sides. For the pro-gun right, they offer a credible explanation for violence that turns attention away from gun regulation and domestic terrorism. For Democrats—already on the defensive—they provide a springboard to pivot back to more important, material issues.

Gamers might not like it, but their hobby is likely to persist as a tool in political disputes about violence. You’d think that Republicans would be worried that they might alienate their constituency—some of whom surely find games appealing—by vilifying the pastime. The fact that the politicians and pundits don’t seem to care suggests that enough older people also dislike games, or that the cost is a minor one, paying generous political dividends to other accounts.

Or worse, both. Ferguson told me about a study he did with adults over 55, who tend to be suspicious of games. “You can have them play a moderately violent game like Tomb Raider,” he said. Asked what they think, they report that they kind of enjoy it. Asked if it would cause kids to hurt one another, they say no. But, he said, “they still believe games in general are bad.”

Games were vilified long before the United States had a mass-shooting crisis, but at least past critics deemed them powerful enough to constitute worthy cultural opponents. Now, for all the corrupting power those on the right want to ascribe to them, video games are not even enough of a force to merit political pandering to the people who play them. They’ve become pawns in other, bigger political battles.