Are Video Games Worth Studying? (A Literary Perspective)

Video games are part of a history that roots itself within the mythic tradition of storytelling. This is a tradition shared by genres traditionally thought of as literary, such as novels, poetry, and drama. Yet despite the lineage that video games share with literary fiction, often there is an imaginary distinction made between video games and the traditionally literary genres. Video games are commonly viewed within late 20th century/early 21st century American culture(s) as a medium unworthy of critical study, but this view is not shared by all gamers, nor is it shared by all literary critics. Why is this the case? Are video games actually worth critical study or are those who dismiss video game studies as a legitimate field of research correct when they assert such claims as “You’d be better off putting down the controller and reading a book?”

(Re)Defining Literature

The traditional view of literature, “written work valued for superior and artistic merit” (Oxford Living Dictionary), is a view that prizes books above all other mediums. It is a definition that naturally connotes a power structure and elitism, albeit it does so in a way that is not necessarily apparent. Whenever we propose the idea that literature by definition encompasses all written works, a select few written works, or a select few authors, we perpetuate a power structure that can regulate and relegate media. The traditional definition creates a system that enables a disproportionate number of intellectuals to judge the quality of all other works. That which fits within the canon’s established view of good quality is separated from that which challenges the canon in unconventional ways.

If our definition of literature is all written works, then anything that is not a written work cannot be literary. Within this understanding Othello, the Fifty Shades of Grey trilogy, The Origin of Species, “The Tell-Tale Heart,” and Hammer of the Gods: the Unauthorized Biography of Led Zeppelin all share equal literary merit, but other media, such as Hitchcock’s The Birds, Spielberg’s Jurassic Park, Tarantino’s Django Unchained are incapable of being literary. Thus, from the perspective of a literary critic who adheres to this definition, written work has a superior literary value, comparatively speaking, because only written works exist as literature.

Examples of canonical authors- all of whom are pictured here ready to defend the world from bad writing. (Source)Yet there are those who would find this definition still too all-encompassing. For some, to posit that Fifty Shades of Grey can be placed upon on the same literary level occupied by the writings of Shakespeare or Poe is to commit literary blasphemy. Within this definition of literature, a clear hierarchy exists amongst written works. Not everything that is written can be literature. Literature instead is an achievement. For a written work to be literary, it must be superior in its artistic form. It must set a new precedent and build upon the tradition that came before it. This is the view where the canon begins to emerge. Certain voices become privileged. Others become marginalized. (This is largely why there are so many white and male voices within the canon and far fewer female voices and voices belonging to people of color.)

Amongst literary critics, historically, it is not uncommon for this canonized definition too to be too encompassing. One only needs to reference the writings of critics such as F.R. Leavis, e.g. The Critic as Anti-Philosopher, and Harold Bloom, e.g. How to Read and Why, for examples of this perspective. Dorothy Parker, Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston may be gifted writers with extraordinary literary talents, but from this perspective, they are not necessarily always considered amongst the Great Authors, the authors from whom the literary standard is drawn and constituted. Instead, this definition subjugates authors to a select few, and even then, this select few is frequently subjugated to a single author, William Shakespeare. This definition utilizes Shakespearean as the literary standard. Anything unlike Shakespeare is not worth reading.

For Harold Bloom, the Bard is not one to be trifled with. (Source)Each variation of literature, from the most anarchic view (all written works are literature) to the most monarchic interpretation (Shakespeare is literature, you plebeian), provides a different assessment of what physically makes a text literary. Central to all three of these varying definitions, however, is that to be literary, a piece of media must either be a written work or directly connected to a written work. This can be and often is the case, but the connection between media and a written artistic text does not always have to be direct. Instead “literary-ness” can come through other avenues, tie ins to social events, human psychology, history, or even what is called literary theory.

Literary Theory

Whereas a definition of literature aims to regulate what should or should not be read, literary theory aims to regulate how a text can be read. It is from this regulation that a reader is able to determine a work’s possible literary meaning(s). Whether an individual is cognizant when making a judgment about a text, that person is influenced by literary theory when creating that judgement. To quote Lois Tyson’s Critical Theory Today, “there is no such thing as non-theoretical interpretations” (4).

To be able to interpret a work in any capacity is to attribute a literary quality to that work. Yet not all works are literary in the same way. That is why it is imperative to stress that there is not a singular theory that enables a work to be literary. There is instead a plurality. Each theory provides a way to “see both the value and limitations of every method of viewing the world” (Tyson 3). No theory yet provides all of the answers, but each literary theory highlights aspects that enables a critic to find at least an answer. Some theories are compatible, e.g Marxism and African-American Criticism. Others are opposed to one another, e.g. New Historicism and New Criticism. Each theory calls a different perspective into study. Each theory gives the study of a work purpose. Without theory, the study of any text, written or not, is impossible.

While the majority of literary theories may not originally have been intended for the video game medium, these theories still can be applied to video games, just as they may be applied to music, film, and other forms of visual art. I can play Resident Evil 4, but I can also utilize the game to explore how it reflects Kristeva’s theory of the abject found in her Powers of Horror or Said’s notion of the “Orient” within his Orientalism. It does not matter particularly which theory I choose to evoke, but what does matter is how I choose to utilize any theory to uncover a meaning from the text. I must be aware of what a particular theory allows me to claim, but I also must be able to state why the sort of claim I am making is important and recognize what conversations I am a part of by making this claim. A worthwhile claim does not depend on whether a given medium is written. It depends on the theory being used to analyze that piece of media.

The Curse of New Media and Hyperreality

I could just play Resident Evil 4 and shoot these villagers without thinking, but I also can stop and utilize this scene to reflect upon some aspect of culture. How does this game tell me it is okay to kill these people but not others in this game? Who are these people exactly? What do they represent? What messages about class and humanity does the game convey based on how it is structured? (Source)There is a reason why video games are not taught in classrooms as frequently as more traditionally “literary” texts like Rome and Juliet, The Hobbit, and The Great Gatsby, but this is not because video games cannot be literary and are unworthy of any critical analysis. Rather, the perception that video games are incapable of being either of these things, i.e. literary and worthy of critical analysis, is what informs video game’s relegation to an inferior form of media and storytelling.

Within contemporary American culture, video games are often perceived as mindless entertainment, usually aimed at children and young men. As such, video games share in the struggle faced by most new forms of media. They are judged in relation to those forms which preceded them and are dismissed as a lesser copy. As a result of this perception, video games have yet to achieve the universally recognized literary status that is attributed to other forms of written storytelling. But this perception is slowly changing. Arguably, the medium we call “the video game” not only deserves to be analyzed on the same scale of literature, it deserves recognition as the spiritual successor to the novel, drama, and comic book as narrative forms. Yet if video games are worth studying, as I claim, why would a perception exist within American culture that so largely contradicts my view? How can it be that video games are worthy of literary analysis if there are so many skeptical voices within the culture at large?

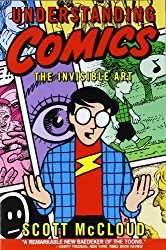

In his most famous work, Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud describes the skepticism and harsh, non-literary criticism new storytelling innovations face as “the curse of new media” (151). While McCloud is speaking about the innovation of the comic book and its public reception as a complex literary artifact, the argument remains the same for video games as well. A mass skepticism towards a medium’s literary merits propels an argument that bases itself around the concept that tradition is a measure of quality through which a person may determine a piece of media’s worth. For many, video games do not meet the standards this tradition has set. For these people, video games are seen as an imperfect copy of what came before them, mass market stories and regurgitated board game mechanics without literary merit.

“Ever since the invention of the written word, New Media have been misunderstood,” McCloud writes, “Each new medium begins its life by imitating its predecessors” (151). The attitude that must be taken then is not to view a medium as a lesser and derivative form of mode of story-telling, but to view a medium as unique and capable of accomplishing particular modes of storytelling that other mediums are unable to. The earliest ancestors of video games expressed themselves through oral narratives and artistic images, but video games utilize more than audio-visual storytelling that rely on the ancestral forms. This in part may be a source of anti-video game skepticism.

Video games provide an avenue that no other literary genre has been able to accomplish thus far, a nearly full immersion into another’s reality. When an individual plays a video game, no matter how constricted the confines the game’s design may restrict a player’s range of choices in-game, that individual is granted an ability to actively participate within the story and guide aspects of the story along in ways that go beyond what written literature has been able to accomplish. Not even the genre of the “Choose-Your-Own-Adventure” novel has been able to rival the amount of creative control a player is able to partake in shaping the narrative. This creative control that a player has while navigating through a video game’s narrative creates a genre of literature that can be described as what Umberto Eco calls “hyperreality” (8).

Umberto Eco, confounder of reality and literary pioneer. (Source)Eco describes hyperreality as those instances where imagination “demands the real thing, and to attain it” someone “must fabricate” an “absolute fake; where the boundaries between game and illusion are blurred, the art museum is contaminated by the freak show, and falsehood is enjoyed in a situation of ‘fullness,’ of horror vacui,” or the filling of every empty space with detail (8). With the exception of graphic novels, which still face a similar stigma shared with video games, all written literary genres cannot approach the hyperreal. No matter how immersive the genre is, there remains an empty space that separates a reader from the work in question.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Written works can definitely alter a reader’s sense of reality and cause certain perceptions about what is real and fiction to blur, but the medium maintains an empty space over character control that only may be found within video games. More so than any experience lived through another’s writing, and certainly more so than those observed within film, the events within a video game create a hyperreal experience for the player.

People who are too young to enlist can experience hyperreal war throughout titles like Call of Duty and Medal of Honor, while law-abiding citizens are able experience hyperreal terrorism through games like Grand Theft Auto, Watch_Dogs, and Infamous. Narratives become a lived through experience that players can share as if they lived these lives directly. I have never lived as a Spartan warlord, but I have distinct memories of killing the God of War and usurping his deified throne. I have never woken up in a lab with only a portal gun to make my escape, but I remember doing so and thwarting a homicidal AI named GLaDOS in the process. I can recall times I have raced through fictional lands, made monsters battle each other on my command, fought at Normandy, led a raid on the Dire, and escaped a zombie-infested place called Ravenholm. This is not the experience that I have had with books.

Having read Anna Karenina, I do not have memories of being run over by a train. Fight Club did not lead to me thinking that I have a second personality called Tyler Durden. I remember other characters who have “lived” these lives, but these experiences do no constitute as my own. House of Leaves leaves me memories about a labyrinthine house, a blind scholar named Zampanó, and the hopeless Johnny Truant, but I do not own these memories the way I own those I have acquired through the hyperreal Half Life 2 or God of War. I may bring my own perspectives to written literature, but I do not take my own unique and hyperreal experiences away from the written literature that I read.

Thusly, the study of video games is not only capable of producing worthwhile information the same way other literary studies can, but it is able to investigate a medium unlike any other. Steeped in the hyperreal, new meanings and theories await our discovery. We should not abandon the book as a medium because there are so many things still waiting to be uncovered within the pages of new and established writers. However, we cannot retreat to books and dismiss video games as a legitimate medium of study without doing a disservice to our own understanding of literary theory within the context of hyperreal new media.

Works Cited

Bloom, Harold. How to Read and Why. Scribner Book Company, 2000.

Eco, Umberto. “Travels in Hyperreality.” Travels in Hyper Reality, 1967. Translated by William Weaver, Harcourt Brace & Company, 1986.

Leavis, F.R. The Critic as Anti-Philosopher. 1983. Ivan R. Dee, 1998.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics. William Morrow Paperbacks, 1994.

“Literature.” Oxford Living Dictionaries, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/literature. Accessed 7 November 2016.

Tyson, Lois. Critical Theory Today: A User Friendly Guide. 3rd ed., Routledge, 2014.

What do you think? .