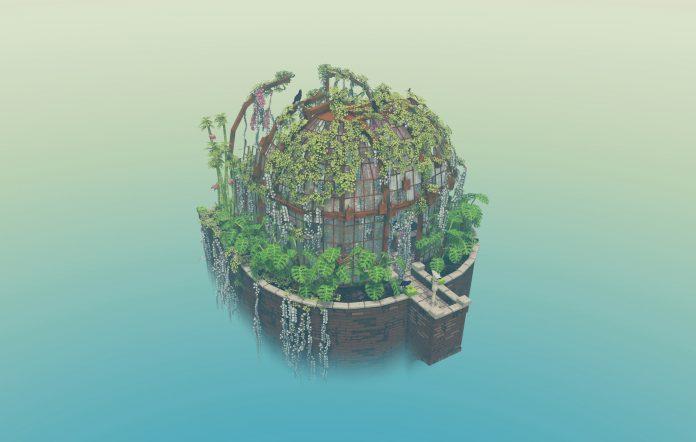

Screenshot: Noio / Kotaku

Cloud Gardens, which left early access last week, is one of those games that is both incredibly difficult and incredibly easy to pitch. The idea is simple—you plant seeds and then place objects which make those seeds grow. Sometimes the object is a beer bottle or a radiator or an apartment or a rusted-out car. It is very simple mechanically, visually breathtaking, and incredibly relaxing. But this describes plenty of video games, most of which were nowhere near my Game of the Year list, especially not two years in a row. That’s because none of them could make me feel, or think, like Cloud Gardens has.

Cloud Gardens could be called a deconstruction. Environmental storytelling has become a big buzzword in video games, often determining whether or not a game feels “real.”. Does the graffiti make sense? Can I reconstruct the last time this room was used by the objects left scattered across the floor? Is the toilet broken? Why is the toilet always broken? It is the quiet stories like this that made me fall in love with games like Umurangi Generation, which uses its environment to craft a fully realized setting rife with all the messy breadth and depth of human experience.

Where Umurangi Generations is great at telling stories through its environment, Cloud Gardens hands those tools to the player, and gently encourages them to tell their own stories. The result is extraordinary.

Screenshot: Noio / Kotaku

G/O Media may get a commission

hi again eric, thanks so much for your help with that water situation at the beginning of january. i, and some of the other tenants i’ve talked to, have been interested in rebuilding that greenhouse on the roof to start a community garden. willing to pay for materials and everything, just looking for sign off! thanks in advance

Environmental storytelling, then, is the art of telling stories about people who cannot speak. It’s what happens when memory fades into the walls of a place, and we try to find any meaning in that uncanny feeling of familiar-emptiness.

Cloud Gardens asks you to place objects to make plants grow. Which is to say that it is a game about constructing environments. You’re given a small square with a white plastic lawn chair. In that chair is a seed. You plant the seed and vines wrap around that now-yellowing plastic. The game offers you beer bottles and you drop them beside the chair, causing the plants to grow and allowing you to complete the level. You tell a simple story by doing this. Someone sat in this chair and drank a bunch of beer, alone. They are gone now.

Screenshot: Noio / Kotaku

Hello Ellen, despite what you and “some of the tenants” believe you do not, in fact, own this building and you will certainly not be making any decisions about potential remodels, especially in spaces for which you do not pay rent. I would politely ask that you keep your messages strictly to the condition of your own apartment as that should be your primary concern.

Lonely stories like this are common in Cloud Gardens. The game is not explicitly post-apocalyptic, it isn’t explicitly anything really, but it does play with the aesthetics of the post-apocalypse. It is all broken bridges, cracked brick, and rusted-out cars. Every apartment is wholly embraced by the plants you place. No person would let this happen, and so you are left wondering how we get here.

In its longer levels, and creative mode, more complex stories emerge as you assemble an environment piece by piece. Characters, and their echoes, start to mark the bricks you place.

Screenshot: Noio / Kotaku

dearest eric, thank you for so graciously, and with great promptitude, deigning to respond to the message of one of your lowly serfs. i hoped that, by obsequiously omitting the fact that you had not in fact ameliorated the january water situation, you would have become more amenable to what seems to be a minor request from a kind and gentle young lady. sadly, this doest not seemeth to be the case. i understand your decision completely and will, as you request, return my focus to my own domain which i, again, so deeply thank you for allowing me to remain within, you fucking leech.

sincerely, your dearest elly.

p.s. your shit ass stepson won’t stop drinking on the roof and its getting kind of gross. he wont like you anymore just because you pretend he isn’t up there. you’re probably why he feels the need to do it in the first place douchebag

But as I have played more, I have started realizing that the feeling doesn’t come from the stories you end up telling with the game’s levels. The relationship is inverted. Cloud Gardens makes me feel, and so I tell stories about it in an effort to make sense of those feelings. But the stories I tell do not always make sense.

This is a common problem in environmental storytelling; you want to get a narrative across and so you place objects to make that narrative explicit. If a revolution is at the gates in your setting, toss up some “REJECT THE SYSTEM” graffiti. The problem is that, in the real world, if someone put really earnest “REJECT THE SYSTEM” graffiti somewhere, they would be rightly clowned on for being corny. If your environment is too on the nose, it will ring hollow. Cloud Gardens is different though. Its stories aren’t too on the nose; rather, they become impossible and illegible.

One of the game’s early levels has stuck with me for a long time. It is a broken patch of highway, a rusted-out car lying amongst the rubble, the blank ribs of a road sign overhead. To complete the level you place the signs that once directed people across the now-shattered road. And so you place the big sign first, and then a smaller exit sign. And then a notice here and there. When I had something that made sense I glanced at my progress through the level. I was about 30% through. I ran out of signs, and the game presented me with dozens more. Notice after notice after notice. Signs pointing in every direction. Imagine the labor hours once needed for this, to bolt every one of these useless goddamn signs to this broken highway that no one drives on any more.

As the actual highway sign lost legibility under the slew of smaller signs stapled to it, so too did the story. There was no slow apocalypse here. A car was not left abandoned in the middle of an already closed highway, painted with signs, and left to rust. There is nothing to reverse engineer here, not really. So why, again, can I not stop thinking about it? This stupid, impossible stretch of road that seems to both invite and reject any reading you try to give it.

Screenshot: Noio / Kotaku

i am become the antifactory. an open plane where nothing is consumed transmuted or produced. my investors ask why i am and the world is undone .

Imagine the apocalypse for a moment. Really imagine it. City infrastructure collapsing, social systems decimated, chains of production broken. It is easier to imagine now, having lived through a global pandemic. Forget the people though. Pretend we’re talking about the rapture. Poof, everyone is gone. Imagine what an apocalypse looks like for the objects left behind.

The office building does not stop existing, it simply loses its human referent. It goes from an office building to a mass of concrete and steel. Perhaps it becomes a habitat, or a greenhouse, or a thing we do not have a name for. It becomes a thing that does not make sense to us.

This is what Cloud Gardens delights in. Removing the human referent from human objects. A beer bottle is not a beer bottle in Cloud Gardens, it is a round thing that makes plants grow. The impossible road signs aren’t supposed to communicate anything to us, they’re just there to construct an environment for plants to inhabit. The plants become the new referential object for Cloud Gardens’ world.

And that’s what the apocalypse is, really. It’s a changing of referents. The assumed default collapses, and meaning has to be reconstructed in a new framework. So yes, Cloud Gardens is post-apocalyptic, but it’s apocalypse is not even about us. The assumed human is gone, and the environments the game asks you to produce end up looking both familiar and totally alien. And goddamn are they pretty.

But that prettiness is not the focus. Even human aesthetics are abandoned. The beauty of overgrowth and ruin emerges from a delicate balancing act; the plants can only cover so much before the melancholy of a broken, but legible, human space goes away. Cloud Gardens frequently demands you go beyond that point. The game’s levels are not about making a pretty space. The literal objective is to make the plants grow enough. It is not about you, or how you want this little tableau to be arranged. It’s about them, the plants for whom you are constructing this space. Prettiness is a fortunate side effect.

But the game does not let itself fall into an eco-fascist trap. It is not saying that the world will be better without people. Instead, it seems to take a more distanced position. By presenting to you this world that is so unmistakably alive, and so clearly built on the aesthetics of social collapse, Cloud Gardens rejects the notion that the end of the world as we know it is a loss, or an ending at all. The world it imagines does not hate people, it just is not built around them. In spite of that, connections and beauty and meaning still emerge.

Cloud Gardens perfectly distills why I am not afraid of the end of the world anymore. Things, regardless of their circumstances or original referents, are drawn to build connection to one another. The office becomes a habitat, the city becomes a forest, capitalism becomes a memory. In all of these scenarios, things and people still live. An EMP could go off tomorrow and all computers could be permanently fried. I love video games, this piece is evidence of that, but it would be all right. The structure of the world would change, sure. But that world would still make us feel things, and we would still be damn good at telling stories about those feelings.